Black History Month: How to Make February Matter

As a Black Canadian scholar, writer, and public speaker, I participate in Black History Month every year. At the end of 2023, I started to receive invites to speak at 2024 events. Some I agreed to, and some inviters declined once I presented my fee — an issue I address later.

I am old enough to remember when there was no Black History Month, and we would sit around complaining about the lack thereof. But every year when February rolls around, I find myself torn about it, especially the way it is presented within universities where Black people often do not have a seat at the table (and even if we do, too often what we say is met with deafening silence or ignored altogether) and our Black Canadian scholars, writers, and critics are not on course syllabi (there is no way to hold people accountable for the lack of diversity on their course syllabi). But these same institutions organize Black History Month events.

Part of the problem is that these events, which are always framed as “celebrations” have become two things:

A poster display or website with a timeline of randomly selected “Important Black people you must know” (when am I going to make one of these lists?!?)

Organizations or offices that do little to support Black people 11 months of the year, suddenly have programming and luncheons to “celebrate Black life.”

What’s often missing is the context to understand why Black History Month was created in the first place. Understanding this history will help to combat fatigue because you will feel as though you are growing roots, so to speak, to understand how Black people — from multi-generation African Canadians, second-generation Caribbean folks to continental African immigrants — fit into the North American narrative. Knowing these roots will also give context to the things Black people do and say. The month is much more than mere celebrations, it is a time to reflect on past, present, and future Black histories.

Carter G. Woodson

I first started writing about Black History Month ten years ago in a piece for Rabble.ca. That article began with the work of historian, educator and intellectual Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950) who in 1926 initiated a week-long celebration aimed to commemorate the lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln (both born in February) who were instrumental in the approval of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery in 1865. He called it “Negro History Week,” and it is the first acknowledgment of Black history in North America.

The week was not about celebration. It was a direct response to oppressive White supremacy that sought to silence, minimize Black contributions and keep children behind in school.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of Carter G. Woodson. 19 December 1915

Woodson’s aim was to create knowledge about Black people with a view toward eradicating ignorance, and most importantly, he sought to uplift the spirit of Black children so that they would have pride in their history and culture.

According to the NAACP,

“After being barred from attending American Historical Association conferences despite being a dues-paying member, Woodson believed that the white-dominated historical profession had little interest in Black history. He saw African-American contributions "overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them."

Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915 in Chicago, describing its mission as the scientific study of the "neglected aspects of Negro life and history." The next year, he started the scholarly Journal of Negro History, which is still published today under the name Journal of African American History.

Black History Month expanded into a national celebration in 1976, in conjunction with America's bicentennial, but the impetus for Negro History Week was to circumvent Black erasure from history, education, and the culture.

Hon. dr. Jean Augustine

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of Former Etobicoke—Lakeshore M.P. Jean Augustine (7 December 2010)

In Canada, Black History celebrations first began in 1950 when the Canadian Negro Women's Association organized events but it was not until 1978 when, in large part due to the efforts of the Ontario Black History Society led by Rosemary Sadlier and others, that Toronto first recognized February as Black History Month. In 1995 Black History Month became a national celebration when the Honourable Jean Augustine (1937 —), the first Black person elected to federal government, brought the motion before Parliament.

Since the 2000s, Black history month has become institutionalized in the sense that schools, workplaces, and public sector employers recognize the month, curate celebrations, and seek out Black speakers to present and/or perform for their employees, students, or clients.

Similar to the erasure of the 1920s racial Black politics from American Black History Month, in Canada, the racism of the 1970s, which directly impacted why the month was created in the first place, is largely glossed over during Canada’s Black History Month.

1970s Racism in Canada

William Borders; Special to The New York Times, Nov. 25, 1974

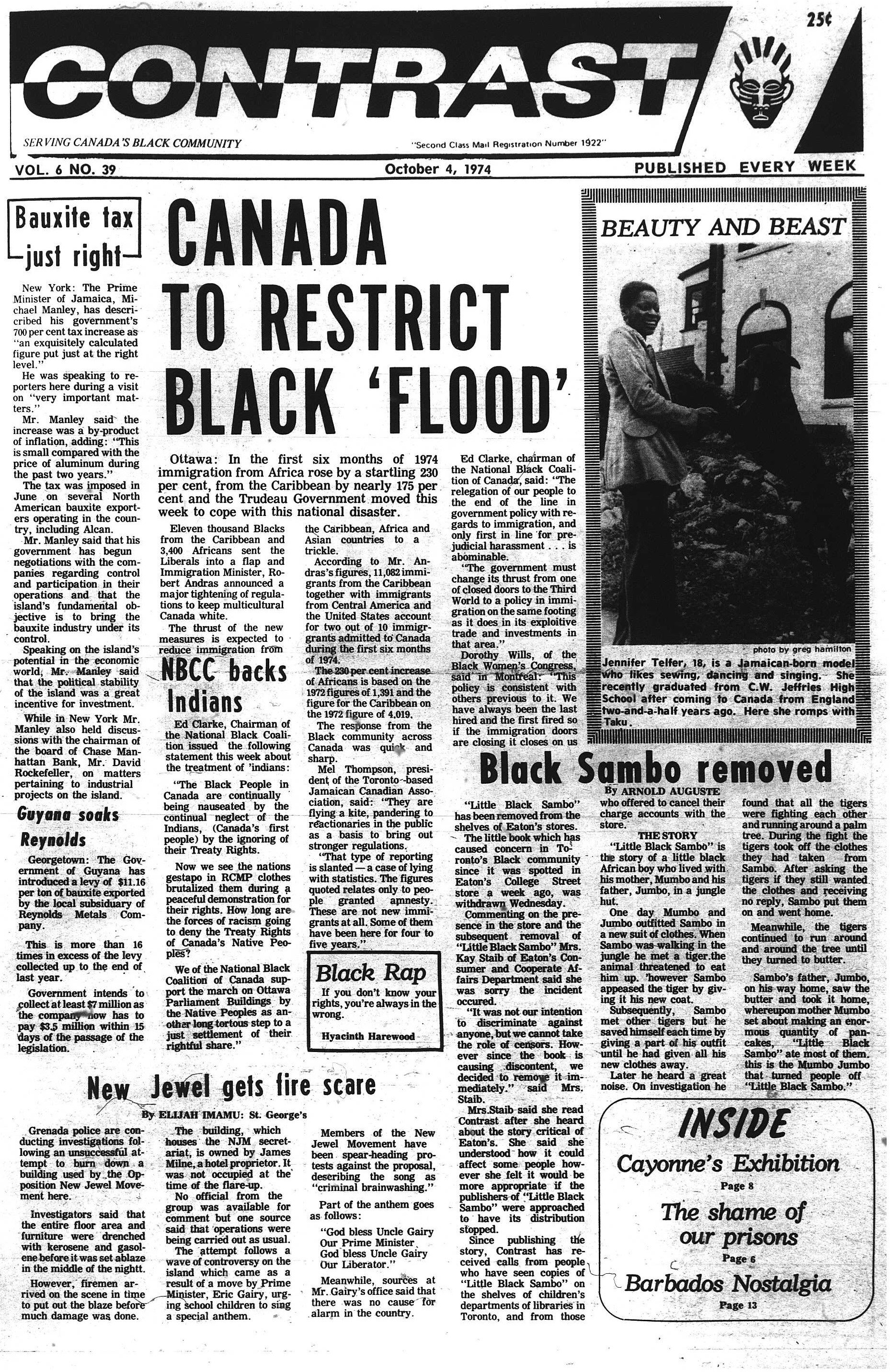

Contrast Newspaper, October 4, 1974

On November 25, 1974, a feature about Canadian immigration ran in the New York Times. Titled, “A Racial Trend in Immigration Is Troubling Canadians,” the article featured several Canadians speaking about the growing problem such as this one:

“Ann MacDonald, widow who lives in a little old house in a part of Toronto that is shabby but still proud, has grown worried and afraid. Her fear tells the story of what is emerging in Canada as an agonizing national debate,” asserted the Times, adding, “Foreigners have always been welcome in this country, and we thought we had a very tolerant society,” Mrs. MacDonald explained. “But the way they're coming in now, they're changing the whole nature of the place and I just don't know if that's what I want” (New York Times, 1974, p. 2)

This story from 50 years ago speaks to the xenophobic, racist mindset of many Canadians at the time regarding Black people and all non-White immigrants. The story continued:

“What concerns people like Mrs. MacDonald is the sharply higher proportion of blacks and Asians among the immigrants to Canada, who used to come almost entirely from Europe and Britain. To a society that has traditionally been nearly all white, the new immigrants are bringing in unaccustomed racial diversity — and some racial tensions, as well” (New York Times, 1974, p. 2)

Connecting Past and Present

Most Canadians in leadership roles today — in our universities, in corporate Canada, and the public sector — were likely born or grew up in the 1960s and 1970s. They remember or have selectively chosen to forget the pervasive racism of that time. And yet, when it comes to Black History Month, too many of these folks are at the helm of planning committees. We absolutely must acknowledge19th century anti-slavery trailblazers through to 1950s changes to Canadian immigration, but the month needs to give much more attention to the realities of the 1970s that Black Canadians experienced as these histories directly impact us today.

By creating a historical fissure in the minds of young people (those born 1980 and after), who do not remember the 1970s, the WHY behind Black History Month can feel unclear. I believe this is the reason so many young Black students aren’t interested in the month or they don’t see any value in its existence. They are not getting the whole picture from our education system. Further, there’s the issue of asking Black people to fill in the gaps, so to speak, with our time, stories, and too often we are asked to do so for free.

Emotional Labour

In an article for CBC last January, Evelyn Bradley, a diversity, equity and inclusion consultant based in Charlottetown, P.E.I. decried, “Stop asking Black people to perform emotional labour during Black History Month.”

“What I've noticed is an attempt to respect Black people by asking them to do more labour — asking them to burn themselves out to teach people about racism and share about all of the trauma Black people face. Black people should have a platform during Black History Month. But I would be remiss if I didn't ask the questions that have been on my mind: When did providing a platform become yet another form of oppression and disrespect? What does it mean to celebrate Black history at the emotional and physical expense of Black bodies?,” Bradley asked.

Bradley goes on to make several astute observations related to compensating Black folks for our time, what it means to be an ally to Black folks during February, and the fact that Black people can say NO to speaking offers:

“Blackness exists 365 days a year and to overwork your Black community for 28 days as a way to show compassion and a readiness to listen to the needs of Black people is an oxymoron. You cannot say you value someone while taking advantage of them,” asserts Bradley.

What Does Rewarding, Uplifting, Community-Building Black History Month Programming Look Like?

We need to acknowledge the fact that Black people are here. We have been through so much in this country, and it’s not about dwelling on the struggle narrative, but we must begin to use February as a moment to acknowledge the obstacles we, as a community, have had to endure and are still working to overcome. Instead of focusing singularly on slavery during the month of February, we need to hear and share our immigrant stories even those Black Canadians who have been here since the eighteenth century — these communities were here before Canada was a country!

Source: Unsplash

Black History Month needs to recognize the diaspora of Black people who are here, not try to homogenize our experiences.

If you do not identify as Black, you can do your part during Black History Month by listening. Literally, all you need to do is listen. Listening to the experiences of others is such a vital part of one’s personal growth trajectory and too often we focus on dialogue but not the act of listening — with one’s heart, spirit, and open mind.

Black History Month offers an opportunity to listen and learn from black people’s experiences and stories — not a time to suddenly discover that we’re here.

Finally, as someone who has curated Black History Month programming (more about this on February 12), it’s important that employers give organizers — which should not singularly comprise Black people, but I do believe it’s important that we play a visioning role — a respectful budget to plan and organize events, pay Black speakers what they ask for, and start organizing months in advance of February, not during the first week of the month when you realize you have forgotten to plan something.

If you want successful Black history month events, you must have a budget, plan ahead of time, and set your intentions for the outcome.

Black History is History.